By Jared Strange, Director of Education and Community Programs

Research by Lizzie Taylor, Senior Development Manager, and Jared Strange

Published March 4, 2024

This Tuesday, Tony-winning hit The Book of Mormon begins a two-week run at The National Theatre. Co-creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone, the brains behind South Park, have never shied from controversy, and their satirical tale about two well-meaning Mormons getting in over their heads while on mission in Uganda is no exception to the rule. It’s hardly the first show to come to The National with a history of ruffling feathers. Subscribers to our newsletter might remember a feature highlighting another musical sensation that was ruffling feathers on its way to the capital: Charles M. Barras’ The Black Crook.

Today, the debut production of The Black Crook is known mostly to historians, some of whom mark it as a prototype of the American musical, a show that integrated song and dance into the story in a way none had before. The story follows a young man named Rodolphe who makes a Faustian bargain with a sorcerer named Hertzog—the so-called Black Crook—in pursuit of his lady love, Amina. Wicked Hertzog is using Rodolphe to activate the powers of Zamiel, a devil who will grant Hertzog immortality if he provides him with fresh souls to devour. With the help of the fairy queen Stalacata, Rodolphe is rescued, and the Black Crook is brought to grim justice. The show was pure melodrama and better known in its time for impressive production values than literary merit. Nevertheless, it was a massive hit when it debuted in New York in 1866, enjoying what was then an exceptional sixteen-month run.

In addition to the ingenuity of its stagecraft, The Black Crook benefitted from a salacious reputation. The controversy arose around the show’s balletic components, which came about when a theatre fire ruined producers Henry C. Jarrett and Harry Palmer’s plans to showcase a troupe of elite dancers they had just brought to New York from Europe. Thinking quickly, Jarrett and Palmer approached fellow producer William Wheatly about leasing the Niblo’s Garden theatre; Wheatley agreed, and the trio set about mounting Barras’ The Black Crook, with the troupe integrated into the show as dancing fairies and other mythical creatures. The women’s beauty and attire (bare necks and arms, short skirts, flesh-colored stockings) scandalized some onlookers, including author and humorist Mark Twain, and is credited for energizing the field of burlesque. However, the show had its defenders, many of whom deferred to the troupe’s European pedigree as being indicative of high art rather than lowly smut.

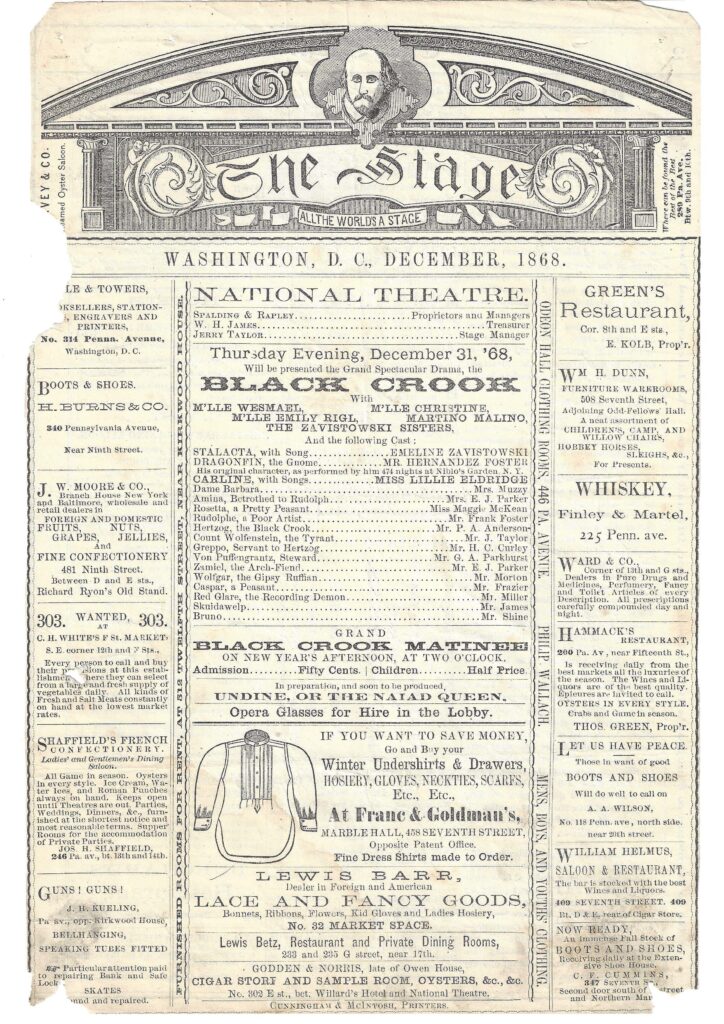

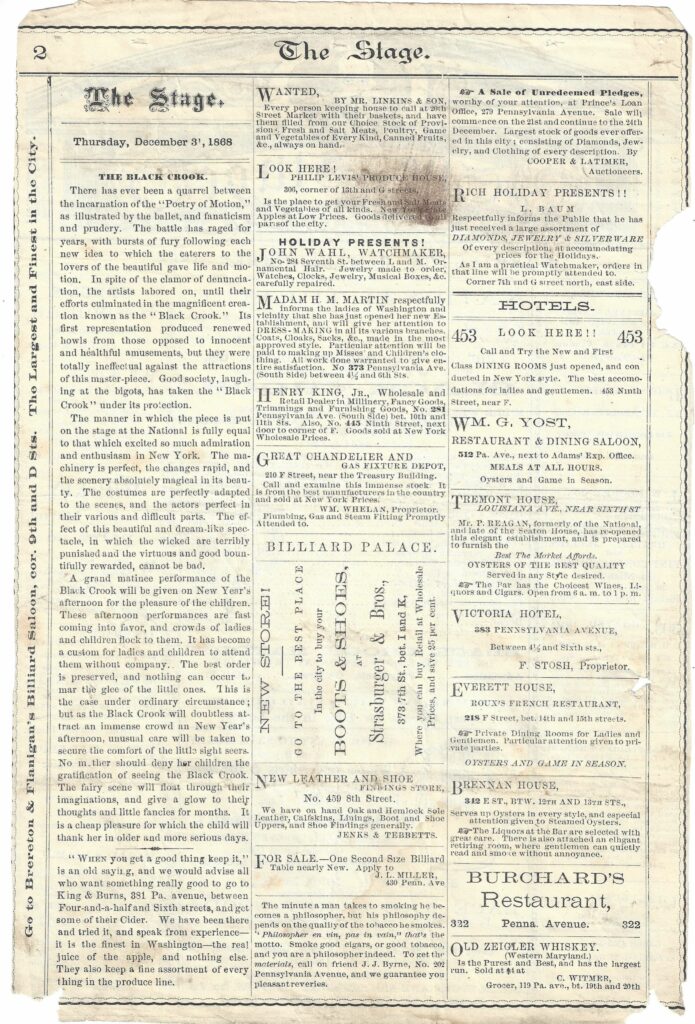

A copy of The Stage program for The Black Crook performance at The National Theatre on New Year’s Eve of 1866. A note bullishly defends the production from critics who were offended by its allegedly risqué content. Note a few features still familiar to theatre-goers today: a list of characters, extensive production credits, and yes, advertisements!

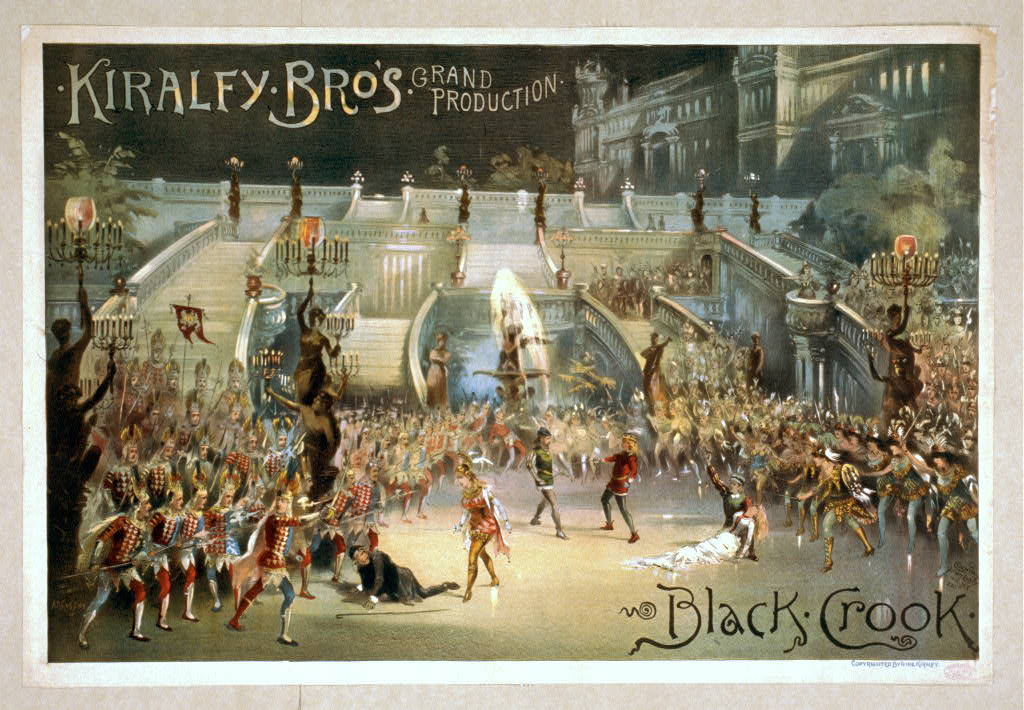

The Black Crook’s reputation preceded it to The National Theatre, where it played on New Year’s Eve 1868. Like countless shows before and since, the production left its imprint on the Archives. The above copy of The Stage, a publication akin to today’s Playbill, is a program for the performance given that day. A note on the second page describes the artists behind The Black Crook persevering in their work despite “renewed howls from those opposed to innocent and healthful amusements.” It goes on to assure readers that this performance, a matinee aimed specifically at ladies and children, “is fully equal to that which excited so much admiration and enthusiasm in New York” and more than suitable for young viewers. “The fairy scene,” it proclaims, “will float through their imaginations, and give a glow to their thoughts and little fancies for months.” It was not the last time the show would come to The National: a new production staged by the Kiralfy Brothers (Imre and Bolossy) arrived in 1882 and returned the following year. By then, the focus was still very much on the dancers: The Washington Post praised the choreography while admitting that the “years [had] robbed the dramatic portion of the ‘Black Crook’ of whatever interest it may have once possessed.”

So, what to make of The Black Crook and it’s time at The National? Perhaps more significant than its content is the influence it had on the development of musical theatre as we know it. For scholar Bradley Rogers, it all comes back to dance. At the time The Black Crook debuted, it was customary in melodrama for performers to strike dramatic tableaux vivants, or static poses, to punctuate the action. By dancing rather than freezing, the troupe (literally) got the artform moving in an exciting new way. As for the performance described in The Stage, one suspects the show was never as ribald as critics claimed (or perhaps this particular performance was toned down for the ladies and children). Whatever the case, the note in The Stage is striking not only for what it says about The Black Crook but what it says about The National’s continuing programmatic interests. Over 150 years later, The National still hosts renowned productions on the mainstage, engages the community through educational programming, and offers free performances to young audiences. That’s why objects like these are so valuable: they keep us connected to a world that is not as removed from the present as we might think.

Works Cited

“Amusements.” The Washington Post (1877-1954), October 30, 1883, ProQuest Historical Newspapers The Washington Post (1877-1990), 2.

Brockett, Oscar G., and Franklin J. Hildy. History of the Theatre. Boston: Pearson Education, Inc., 2008.

Reside, Douglas. “Musical of the Month: The Black Crook.” The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, June 2, 2011, https://www.nypl.org/blog/2011/06/02/musical-month-black-crook.

Rogers, Bradley. “Redressing the Black Crook: The Dancing Tableau of Melodrama.” Modern Drama 55, no. 4 (2012): 476-496.

Stearns, William. “ ‘The Drama Is—Rubbish’: The Early Impact of ‘The Black Crook,’ the Shocking and Scandalous American Musical.” Readex, May 15, 2019, https://www.readex.com/blog/%E2%80%9C-drama-%E2%80%94rubbish%E2%80%9D-early-impact-%E2%80%98-black-crook%E2%80%99-shocking-and-scandalous-american-musical.