Written by: Lana Mason, Archivist

Published: 2/17/2023

For much of the United States’ history, theatre was both implicitly and explicitly a racially segregated environment. The National Theatre, like other white-owned theatres in the South, maintained segregationist policies during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

When The National opened in 1835, Washington, D.C. was governed in part by “black codes” a series of laws severely limiting the freedoms of Black citizens, free and enslaved alike. Indeed, if any Black person was caught in the streets at a given time without the proper paperwork, they were legally deemed runaway slaves and subject to arrest. By the time The National Theatre opened, the codes had only just been modified to allow Black people in the streets until 10pm at night. Despite this adjustment, Black patronage at The National was further limited to certain seating sections, meaning the house may have been “open” but it was still internally segregated. This remained the case until 1873, when The National was rebuilt following a fire and effectively barred Black patrons from entering at all, putting it in line with other major D.C. theatres.[1]

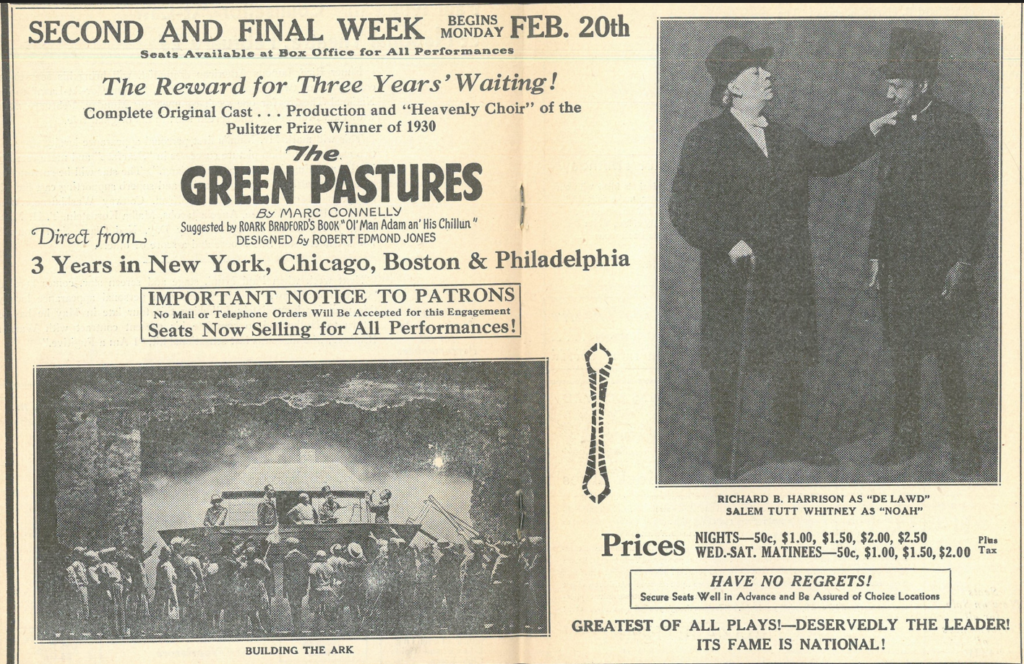

Despite the fact that Black patrons were prohibited from attending shows at the theatre, Black performers were still permitted to act on stage. There were several all-Black productions which toured at The National prior to its full integration in 1952. These productions were well-received by the white critics and audiences which attended them. One of the most popular Black productions to visit The National during segregation was the 1933 run of The Green Pastures.

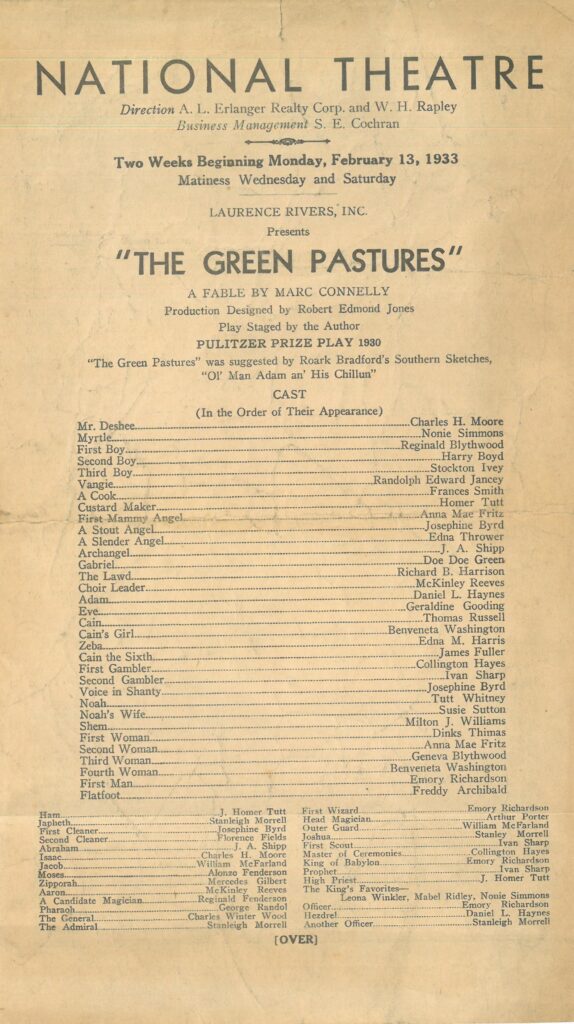

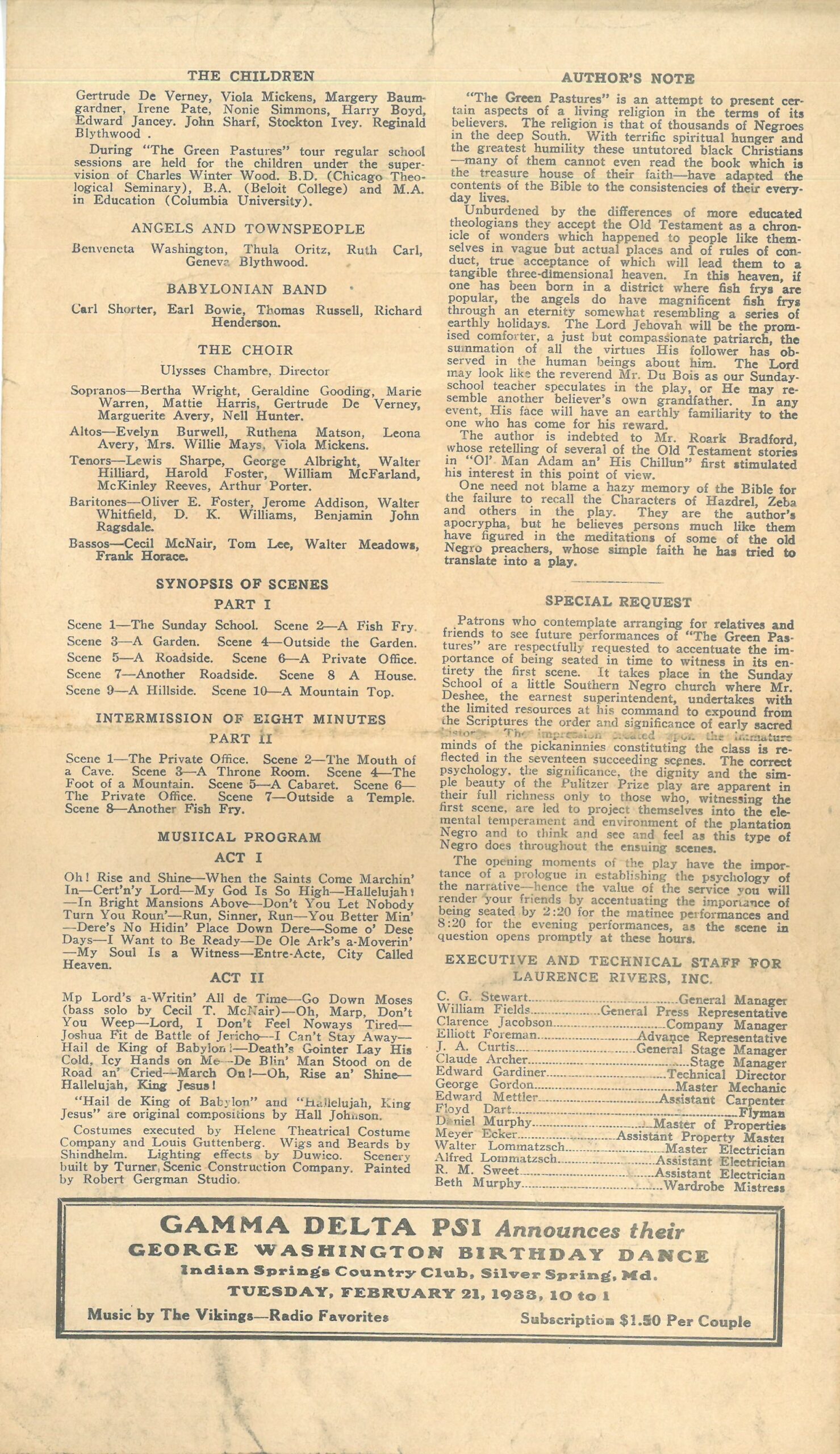

The Green Pastures was the first Broadway production to feature an all-Black cast. It was written in 1930 by playwright Marc Connelly, who was white. The play is an adaptation of a collection of modern folk stories titled Ol’ Man Adam an’ His Chillun, written by Roark Bradford, who was also white. The Green Pastures’ plot centers around the reenactment of stories from the Christian Bible’s Old Testament. These stories are staged within the context of a modern Sunday School session at a Black church in Louisiana.

The play’s cast featured many notable Black performers.

Doe Doe Green played the role of Gabriel in The Green Pastures. He was an actor known for his talents as a comedian. While he primarily performed in vaudeville and Broadway, he also acted in the 1931 film Enemies of the Law.

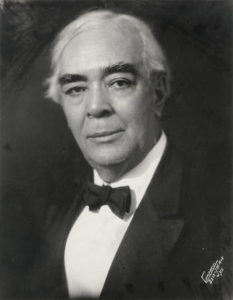

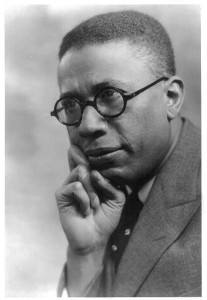

Richard B. Harrison played the much-lauded role of “de Lawd” in The Green Pastures. Harrison was born in Canada to parents who had escaped from slavery in the United States through the Underground Railroad. He worked as a drama editor for the Detroit Free Press and performed as a dramatic reader of plays and poetry. He also taught dramatics at several colleges. The Green Pastures was his first and only role in a major stage production. He performed in the play over 1,650 times.

Daniel L. Haynes played the role of Adam. He was both a stage and film actor as well as (later in life) a Baptist minister. In addition to breaking ground with The Green Pastures, Haynes also starred in the 1929 film Hallelujah, one of the first all-Black movies produced by a major film studio.

Composer Hall Johnson arranged the music for The Green Pastures. Johnson and his choir, the Hall Johnson Choir, were celebrated for their performance in the play. Johnson went on to arrange music for and conduct his choir in various films, short films, and cartoons. He also wrote the folk opera Run, Little Chillun as well as numerous musical compositions.

Susie Sutton, a singer, dancer, and actress, played the role of “Noah’s Wife.” She founded a vaudeville troupe, the Susie Sutton Company, in 1926. Sutton was known for both her dramatic and comedic performances and received high praise from critics for her role in The Green Pastures.

Salem Tutt Whitney and J. Homer Tutt, known as the Tutt Brothers, were performers, writers, and producers who both played in The Green Pastures. Homer Tutt performed in several roles, appearing first as “Custard Maker,” then as Ham (one of Noah’s sons), and finally as “High Priest.” Salem Tutt Whitney played a single, more prominent role as Noah. The brothers got their start in the performing arts with the variety tent show Silas Green from New Orleans which they created, operated, and performed in from 1888-1905. They also produced numerous vaudeville revues, acted in films, and performed comedy.

Though it featured an all-Black cast and focused on Black Christianity, the play was understood to be “designed strictly for white patronage.”[2] And it was so popular with white audiences that its run at The National was doubled in length—from one week to two—to accommodate eager theatregoers.

But The National’s segregation policy, which permitted only white patrons to enjoy The Green Pastures, sat poorly with both the production team itself and with Black residents of the city. The National Theatre’s management engaged in a “prolonged negotiation” with representatives from several local Black social and political groups, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.[3] The groups argued in favor of permitting integrated audiences for the show’s full run. They were supported by the play’s author, Marc Connelly, and Rowland Stebbins, the show’s producer. Connelly and Stebbins wrote a letter to The National’s management which read:

Inasmuch as ‘The Green Pastures’ has played to 1,500,000 persons, whites and Negroes, in all parts of the United States, none of whom has ever raised the question of Negro exclusion in the theatres in which it has appeared, we wish to protest against the reported exclusion of Negroes from the National Theatre. . . While we are informed that there are no legal steps we can take which would confirm our disapproval of this exclusion on the part of the management of the National Theatre, we wish to state emphatically that, if this exclusion is proved to exist, no other plays with which we may be associated will play the National Theatre if we can prevent it.[4]

While management of the theatre ultimately refused to integrate the show’s full run at The National, an integrated showtime was permitted for the final night of the production’s run (February 26). Black patrons sat alongside white patrons, and the show was made a benefit performance for the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. This final night of the show’s run marked Harrison’s 1,215th performance as “de Lawd”—the audience gave him a standing ovation to commemorate the occasion.[5]

References:

- Strange, Jared. “Desegregation.” National Theatre, National Politics. Accessed February 16, 2023. https://thenationaldcpolitics.org/desegregation/

- “Newspapermen to See Negro Play.” The National Daily. The Washington Times, February 7, 1933. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1933-02-07/ed-1/seq-22/

- “Negro Ban Lifted on Green Pastures.” Amusements. The New York Times, February 10, 1933.

- Ibid.

- “’Pastures’ Ovation is Given Harrison.” The Washington Post, February 27, 1933.